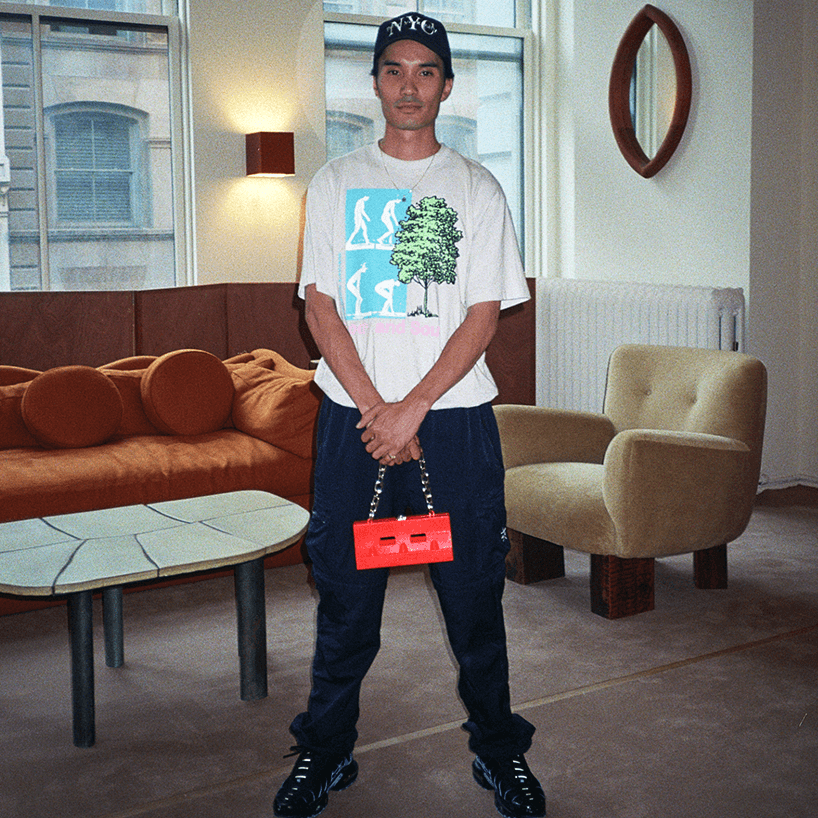

Chris Luu Turned a Barrier Into a Bag

Chris Luu with his creation.

The (sub)culture on which this media enterprise focuses is well regarded for the creative spirit that it fosters, but let’s be real: making stuff, actually taking an idea and turning it into a real thing, can be extremely challenging. We spoke to Chris Luu, who recently took the novel (and very skaterly) idea of producing a small-scale replica of a traffic barrier that doubles as a handbag and really, actually, legitimately made it happen.

Village Psychic

So like…do you skate?

Chris Luu

Yeah, I skate as much as I can, but these days with a full-time job living in New York, I'm lucky if I get out once or twice a week.

VP

What do you do for work?

CL

I'm an art director. I work at an agency called Wieden+Kennedy. In short, I'm responsible for the visual communications of brands.

VP

Is that always what you wanted to do?

CL

I originally started off in architecture, I did four years of that. I got to the end of the four years and I was an intern for a little bit, my first job was circling pipes on floor plans. I would just do that every single day. I remember asking my boss, “How long do I have to do this for?” He just said “As long as it takes.” I remember from then I was like “I don't know how much longer I can do this, and I really don't know if I can do this for the next 60 years of my life.”

I don't know if it was the mentality of the head honcho that was running the place, but I think it was this really old school mentality of, you know…you're really going to serve your time before you get to the big stuff, designing stuff. I also just wasn't truly passionate about it. I really liked learning about it, I just didn't enjoy actually doing the day-to-day stuff. There's a lot of boring jobs in between.

The barrier bag in use.

VP

How did you move on from working in architecture?

CL

I went back to uni at Curtin University in Perth, I think I was like 22, and I was in class with a bunch of 18 year olds and back then, that four year gap felt huge.

Still, I remember just thinking that I had one more shot at trying something new. I wanted something that was creative, but also something I could take anywhere. I remember thinking that I wanted a job where I could potentially can be on a beach and still get paid. Advertising was the closest thing, my neighbor had done it and he made it sound really easy. Now having spent time in it, I just realized you're in an office all day. But overall, It's really great so far. It's far easier (than architecture) in my opinion.

VP

Were you skating during that time as well?

CL

Yeah, I was probably skating the most in my lifetime at that point, because you just have so much time at uni. You get like six weeks in between semesters and then at the end of the year, it's like three months off.

I'd work and skate over the summers and then mid-year when it was winter in Australia I'd always go to the other side of this hemisphere. I had a bunch of friends in London at the time that I always try to visit and just go skate. Going over for six weeks and just crashing with friends was so much fun. I rarely get more than a week off these days.

VP

Getting into making stuff: have you always been somebody who has ideas turns them into real things?

CL

Yeah, definitely. I used to make these really crappy zines with a point-and-shoot camera. I think making those was my earliest experience of making something where I thought “This is interesting.”

I think it was actually during COVID, but I went back to Australia after living in New York for a little bit and it was at that point I started to feel like I had learned how to translate thinking from my day job into side projects. COVID was such a boring time that all there really was to do was make things or just sit at home and do nothing. What I’d enjoyed during my time in architecture was designing things, and because of that I've always had an interest in making something physical. The process that I'd learned inside of advertising was to start with a brief, move into concepting with as many ideas as possible, picking the best one, and then moving into producing it.

After that it becomes the question of “How do I present this to the world?” Which is where the art direction comes in.

VP

What skate references come to mind when we talk about barriers?

CL

I saw a clip recently of Aaron Herrington lipsliding one from flat, just at the SoHo curb spot. That was sick. Another really cool one was this Australian guy, his name's Alex Campbell. He ollies one then crooks the second one in a line, and they’re the thick Australian ones.

VP

When we're talking about the barrier bags specifically, what was your concept around that?

CL

To a regular person, barriers are such an eyesore. They’re just this symbol of impermanence. But to us as skaters, we kind of see a lot of fun in them. They’re this object that is movable, they look great in footage, they can be turned on the side. There's so many different ways to skate them. The one I modeled is a YoDock 2001MB barrier system, and just being aware of different barrier types is pretty skate-behavior.

I've kind of always imagined, like anytime I see one, I always start thinking “How fast would I have to go to hit it lengthways?” To me they just seem like an object of fun, and something I always notice as well. Especially being here in the city, you start to notice all the barriers, and start realizing not all barriers are made equal. Some are different heights. Some are thicker than the others. I've always thought that was kind of interesting.

When I was first thinking about all this, I was thinking of making a small bag of some type, something that wouldn’t cost much money to make because of its small surface area. Also, I knew I wanted to make something plastic because I knew how to navigate a 3D printer. From there, I think I just merged the two worlds together and just thought, “All right, what if I make a barrier bag. That’s interesting,” I enjoy things with tension to them, I like things that have a high and low in the same sentence. From there it started like a six month process of actually figuring out how to actually make this thing.

VP

When you talk about 3D printing, was it like the initial version of it was something that you had 3D printed?

CL

Yeah, I think so. The original drawing of it was literally just a photo of a barrier with two straps drawn on it that I had sent to my friend Jack Morellini who I make a lot of things with under HEAVY DUTY.

VP

Was it challenging actually getting them made?

CL

Figuring out the process took longer than I imagined. It made me realize how hard making things into a finished product would be. The first iteration of it I sketched it up with the help of a 3D designer, originally I intended to glue hinges to it. The versions that came back never worked. It seemed cheap and too “handmade” with faults everywhere. The second iteration, which came a little bit closer, actually involved designing a hinge to be printed in place. That took a bit of figuring out,– you see hinges every single day, but you never really think about having to design them into a product.

The hinge took a bit of figuring out because there were all these little incremental changes. There was like a 0.2 millimeter gap in between the hinge that needed to be separated, and the corner parts had to be straightened off so there was room to rotate — All common sense but make no sense when I was designing it.

After a few rounds of going back and forth, the 3D designer and I finally got it correct. And from there it was just a case of finishing touches. It was a lot of fun to figure out, but it essentially took six months of just poking the project with a stick.

VP

Did it feel like there were any big lessons you learned from the process?

CL

It gave me respect for industrial designers, because it made me realize how hard it all is. Even now, I look at flatware, like a knife on the table, and I'm just like “How the fuck did they make that? Where do they get the funding to make knives? How did they even get this into a store?” I wonder how many rounds it must have taken for one fork to get designed and made.

Another thing that really stood out to me during this process was how sensitive every incremental change is to the product. In my day-to-day job as an art director, I do have to do a little bit of graphic design and a lot of fuss is made over the kerning of letters and type.

I always think it's something that we all feel, but we don't necessarily see, you know what I mean? You can tell when a word is badly designed, but you might not know why. It does feel cheap in the very end if it's designed badly.

VP

What did you learn about 3D printing in general?

CL

It was an important process because I was able to make cheap models that could be quickly made as I worked through the kinks. Then the finished products that I actually made, they're still 3D printed because I could just do them at a lower quantity with a way better resin that’s far stronger than the prototype ones.

Another interesting thing I've learned about 3D printing is how many different types there were. I didn't realize that you can 3D print gold and silver. You can even 3D print sugar. I know someone that 3D printed a crème brûlée. It's insane.

VP

Regarding the non-skate audience, what do you think people who don't skate might think of the bag?

CL

I think a lot of skaters just sort of understood that it’s something we see every single day and that I made into a purse. But then a person that doesn't skate, I think it's really interesting because people tend to gravitate towards familiar objects and I think that this goes back to what I was saying before about the tension of it. Taking a street object and turning it into a fashion accessory is visually interesting to people who don’t skate.

VP

Is there a plan to get them out to a wider audience?

CL

They’re being sold at my friend Frank’s store, Leisure Centre. It's on Hester Street on the Lower East Side, it's a really cool store. It's worth supporting, they're very friendly people. Go in, say “Hello.”

But having friends hit me up for it was so sick. People wanting to own one, is a satisfying feeling.

VP

It's no small feat, getting to the point of actually getting something out of your head and having it made. Sometimes it doesn't even matter what it is, just being someone who can do that is a huge reward.

CL

You're so right. I think that’s also a big part of why I really enjoy doing stuff like this, because we all have so many great ideas, but actually realizing them and seeing them in person is hard. You don't really see the years of process or however long it might have taken you to get there. All you see is the end product and now it's there in the world forever.

VP

Especially living in New York, you can get kind of numb to it – another art opening, another person showing something off. When you make something yourself, you get reminded that someone worked really hard and spent their time and actually made a thing.

CL

I always think about my friend Garth Mariano who has three brands, Butter, Lo-Fi, and Cash Only. When I first met him 10 years ago, he was just making t-shirts. It’s grown into them learning cut and sew, homewares and experiments. It’s inspiring to see him and his team actively trying to make new and fresh things. It’s nice to be surprised.

VP

Do you have other stuff like that you want to do?

CL

A lot of what I do day to day is very 2D. Delving into 3D is such a new language. It's really great to learn something different. I'm learning to make jewelry, still in the 3D world but working with new materials and a completely new set of people who kind of know this craft. We're working with molds and pouring, an unusual process for me.

I guess my end goal is just to get into that nebulous zone of creative consulting. It would be so great to be the creative direction consultant who gets into a room and with a bunch of clients and whenever someone shows you an idea, you can just say “That doesn't scare me.” And then everyone just starts clapping.